This article was originally published by Super Interessante, and can be retrieved at https://super.abril.com.br/especiais/o-mundo-pos-coronavirus/. The original article is in Portuguese, and translation into English was done using Google Translate.

Winston wakes up, gets out of bed and turns on the TV to take a gym class. After stretching, the teacher asks who can touch the toes without bending the knees. “Only the waist. One two! One-two! ”, He says. Smith tries, but fails. On the other side of the screen, the woman warns him: “Smith! Lean more, please. You can do more than that. Lower. That's better. Now, everybody, rest! ”.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, many people started exercising at home with YouTube videos. But the episode above is over 70 years old. It was written by George Orwell in 1948, when the first TVs appeared, long before the internet. In the 1984 novel , the State uses “teletelas” to broadcast political propaganda (and also gymnastics classes) all day long - and monitors its citizens 24 hours a day.

When the coronavirus pandemic is overcome, a new world will be born. Politics, economics, health, science, human relations: many things will not be the same as before. It is very likely, for example, that you will be monitored in real time by the State, which will use data to determine what you can and cannot do. It is something that even Orwell's fertile imagination could not conceive - but it has everything to happen. Even because it's already happening.

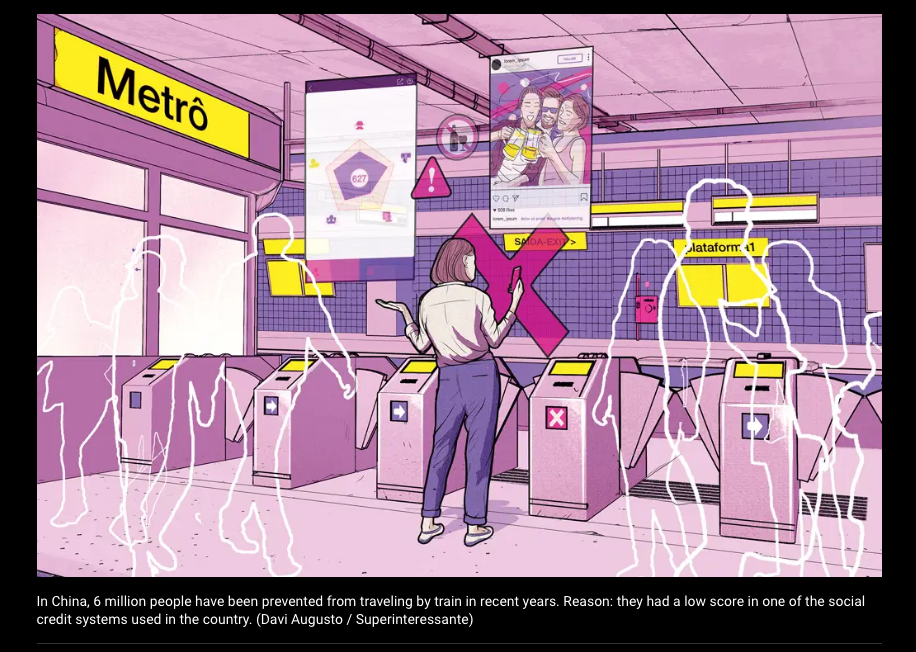

It works like this: each citizen receives an initial score, which increases or decreases according to their conduct. Those who do well in their studies, donate blood or volunteer, for example, earn points. Whoever crosses the street loses points, walks the dog without a collar or delays the payment of taxes. China uses 200 million surveillance cameras, connected to a facial recognition system, to collect data on the behavior of each citizen. “It is a little reminiscent of the Boy Scout culture, with its social values. But in the digital world, I would say that it is the gamification of life ”, says Gil Giardelli, professor at ESPM and a member of the World Federation of Future Studies (WFSF), based in Paris.

A high score makes life easier to finance a property, rent a car, get better jobs or enter a good university. A low score can restrict access to public services and prohibit people from traveling - by June 2019, according to the Chinese government, 26 million airline tickets and 6 million train tickets were denied to people who had low scores (they had money to purchase tickets, but were prevented from buying them).

Currently, there are several social credit systems, which are managed by Chinese companies and local governments and adopt different criteria - but they must be unified. “The idea is for the central government to carry out a study and think about a policy that expands to the rest of the country in a uniform manner,” says Evandro Carvalho, coordinator of the Brazil-China Studies Center at FGV Rio. In 2018, an online study done by German researchers with 2,209 Chinese revealed that 80% of them approved the social credit systems they used. Detail: all were private systems, created by companies. Among the most popular is Sesame Credit, from retail giant Alibaba, which uses algorithms to determine who can and cannot take a loan - at least that is the proposal. But only 11% of Chinese knew that the government also has its own social scoring system. For Carvalho, the concept of social credit led by the State is more linked to economic aspects than to the restriction of individual freedoms. "Stability is fundamental in the life of the Chinese, and the social credit system is especially about productivity," he says.

But international observers, such as the American NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW), say that social credit may have a more sinister side: the Chinese government, which already monitors the internet heavily, could increase or lower citizens' scores according to the sites they access, with whom they communicate and what they post. It would be a way to relentlessly control the population's ideology. "For the time being, political criteria are not included in the system, but there is little to do," says Kenneth Roth, director of HRW. And the thing goes further: in the future it will be possible to use even biometric signals, such as heart rate and body temperature, to monitor people.

Not in the future. In the present even. The coronavirus accelerated and deepened the monitoring process. In several cities in China (and the rest of the world), the entry and exit of people in buildings is controlled: inspectors take your temperature, and you cannot enter if you have a fever (which is a common symptom of SARS-CoV infection) -2). Access to public places, such as supermarkets, is also being regulated, with data provided by platforms such as WeChat and Alipay. With more than 1 billion users, these super-applications were already part of the Chinese routine, because they serve almost everything: to pay for purchases (replacing debit or credit cards), to request delivery, as a social network and to transfer and receive money.

With the emergence of the pandemic, citizens were forced to download a new app, the Alipay Health Code, which merges data from your health history and the places you've been to assess your risk of being infected. It assigns a QR code, and a color, you - who have to show the code before taking public transport, entering stores or, in some cases, even leaving their apartment. If the status is green, you are allowed to move around in public places. Yellow indicates contact with individuals or regions at risk, and limits the places you can enter. Red means that you may be contaminated, and you should isolate yourself immediately. All of this has helped to contain the pandemic. But it also creates an Orwellian routine, in the best Big Brother style, the figure that represents absolute totalitarianism in 1984- not least because the Chinese government has not explained in detail how its system calculates the color assigned to each person. And this makes room for arbitrariness: in a post-pandemic future, people with low social scores could be punished with an equivalent to the color red, and have their circulation restricted, for whatever reason.

South Korea, cited as a benchmark in tackling the pandemic, is also closely monitoring its citizens: the government uses SMS to report where there are potentially infected people and where they have been recently. When a positive case is registered, the patient needs to answer a questionnaire saying where he has been and with whom he has been. And not only are people who have had contact with him warned, but also strangers who may have crossed his path - like the cashier at the market or the driver of the transportation app. This is only possible because the responses provided by the infected are cross-referenced with credit card data, cell phone GPS and, of course, surveillance cameras - also common on Korean streets. This has also been effective in combating the pandemic. But it’s an unprecedented surveillance standard.

It uses Bluetooth Low Energy technology to map the proximity between people, and it will record all individuals that you have physically approached - and if any of them test positive for coronavirus, you will be informed. The system will be deployed through an update, which will reach basically all smartphones in the world in the coming weeks, and will serve as a basis for applications developed by governments (Apple and Google will not do the tracking; they will only provide the infrastructure for it to occur) .

Russia is also in the ciranda. It has already started to develop a mandatory application that will use a QR code to store data about its citizens. Germany and Italy are using data provided by mobile operators, which allow them to know where each person has been. And the Brazilian government has announced that it will adopt a similar system, monitoring 220 million cell phones. According to SindiTelebrasil, a group that brings together operators, the data will be anonymized and provided 24 hours late, that is, they will not reveal the identity of the people or their location in real time. The idea is to use the information to better understand how the population, in general, is moving.

In Israel, cell phone monitoring ended up giving rise to more aggressive measures. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has announced the monitoring of the location of citizens. Then he closed all courts in the country and started to rule by decree. "The coronavirus killed democracy in Israel," wrote Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari. He is used to dealing with the topic. In his book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century , released in 2018, he dedicated an entire chapter to what he called digital dictatorships. “In the hands of a benign government, surveillance algorithms may be the best thing that has ever happened to mankind. But they can also empower a future Big Brother, ”he writes. For Harari, it is very likely that the Palestinians are already being monitored by the Israelis.

Yes. It is common that, in times of crisis, countries pass laws increasing the power of the state. The problem, as we said, is that some of these measures can become eternal. It happened in the USA after 9/11 in 2001. At the time, Congress passed the Patriot Act, a law that authorizes the government to spy on any American citizen. Originally, it would be valid until 2005 - but it is in force, with minor changes, until today. And the coronavirus has already caused a new blow to the state in civil rights. In March, the Department of Justice (DOJ) sought out US Congressional leaders, suggesting a package with drastic actions. The measures, which have not yet been approved, allow the police to arrest anyone indefinitely, without the right to trial. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orban gained absolute power: now, it can create and extinguish laws without going through Congress. The British Parliament passed a package of laws, no less than 327 pages, that radically increases the state's police and legal power. The measures were called, pejoratively, “powers of Henrique 8o ”- reference to this English king, who in the 16th century ruled the country by decree, following only his own decisions.

In an article written in March, Yuval Harari says that Covid-19 could prove to be a watershed in the history of surveillance. First, by normalizing its use in democratic countries, as we have seen here. Second, because it represents a dramatic transition from surveillance over the skin to surveillance under the skin . The coronavirus will pass, but the trauma it leaves will not; for a long time, society will live with the fear of new viruses. This can be used to add a new monitoring layer.

In the future, we may be convinced to wear a digital bracelet, or a smartwatch, which will measure our body temperature and heart rate and send this information to the government, which will use it to analyze who is and who is not sick. This has a very positive side: it helps to contain eventual epidemics. Most people would tend to accept it, ignoring the sinister side of it - if the government monitors your heartbeat and your internet browsing, it gets to know which news and texts make you feel calm or angry. And from there you can infer, to some degree, about what you think . This ability, combined with social scoring systems, would give governments a truly Orwellian power over citizens.

This scenario, which today sounds a bit exaggerated, can become as common as wearing masks to go to the supermarket - something that nobody did even when the virus had already started to circulate, and became the norm.

Major disasters have the power to accelerate history and make things that once seemed unimaginable become commonplace. But, in the post-coronavirus era, society will not only change “from top to bottom”. It will also be transformed into another plane: how we relate to each other.

But for most of the story, this was a relatively rare gesture, used in specific situations (like closing a deal or checking to see if the other person was armed). Shaking hands with everyone, as a universal greeting on a daily basis, came up with the Quakers, a Protestant religious group, in 17th century England. For them, the handshake symbolized equality between people, regardless of social class. The fashion ended up in the etiquette books of the Victorian period, and ended up being adopted by most people. But not all. In Japan and China, people greet one another by slightly bending their torso. In India and Thailand, they shake their heads with their hands on their chest.

The handshake is not as universal as you might think. And when the pandemic is overcome, it may be even less. “It is already like that in other cultures. The coronavirus tends to reinforce this ”, says psychoanalyst Christian Dunker, professor at USP and author of The Reinvention of Intimacy .

It may also be that, after the pandemic is over, everyone will shake hands again and that's it (that's what happened after the Spanish flu of 1918, after all). But life will not return to normal anytime soon, as it is unlikely that anyone will leave isolation with mental health intact. The point is that the human being has evolved to be intensely social, as this was (and is) a question of survival. Confinement is a daily beating that we give in that instinct. And the mind doesn't like to be beaten every day.

In early March, scientists at Shanghai University published the first major study on the psychological impact of coronavirus. 52,000 Chinese people from 36 provinces and cities were interviewed. No less than 35% had psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, compulsions and phobias (including agoraphobia, fear of open spaces). It is far above the classic average, which is between 5% and 10%. Experts have predicted an explosion in the rates of mental illness during the pandemic. And then.

Let's get out of this very differently than we did. But not just for the worse.

Fake news has infested the world for one simple reason: they work. “People identify with that information, even without foundation. It's almost a crowd, ”says Diogo Rais, professor at Mackenzie University and founder of Instituto Liberdade Digital. The pandemic has had its fair share of false news, but there are signs that the wave is starting to turn. Social media took the first step. In March, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram deleted posts that contained lies about the coronavirus - including messages published by heads of state, such as Presidents Jair Bolsonaro and Nicolás Maduro, and former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. This censorship of social networks, even with protective intent, sets a risky precedent. “As a society, we accept this control, given the seriousness of the situation. But it can be a path of no return ”, says Pablo Ortellado, professor of public management at USP. There is also another factor involved: a certain "evolutionary pressure". Individuals who believe lies, and do not protect themselves against SARS-CoV-2, will be at greater risk of having Covid-19 - and the severe symptoms of the disease may force them to accept scientific truths on their skin.

The primacy of science, by the way, should be another axis of the post-coronavirus world. Under normal conditions, a wrong decision or policy can take decades to show its negative effect. Now, it’s not like that: the bill arrives fast, and it can be very high. "The crisis may represent a defeat for anyone who stands as an antagonist for science and universities," says Ortellado.

This change could reduce another central element of the last decade: ideological polarization. That's what psychologist Peter Coleman, a professor at Columbia University and a specialist in conflict resolution, believes. It is based on two premises. The first is historical: for the first time in a hundred years, since the Spanish flu, humanity has a common enemy - the coronavirus, against which everyone is equal. The other is statistical: figures show that serious events tend to unite people. An analysis by the University of Michigan, which analyzed 850 political conflicts that occurred between 1816 and 1992, found that 75% ended after the appearance of a major shock. Coleman cites American politics after the First World War (1918) as an example, which established a more peaceful coexistence between Democrats and Republicans until 1980.

Elections will change, even in form: in the medium term, they have a great chance of happening online. Internet elections would require a longer voting period, from a week or even a month: it is the only way to prevent power outages, network congestion (online elections are not like Big Brother voting, they require tough security systems) or other technical problems prevent people from participating. Voting without leaving home could trivialize elections and generate controversy, since there is no way to recount the votes. The solution may lie in technologies such as Blockchain, a database virtually impossible to defraud. It has already been used for US military personnel outside the US to vote in the 2018 elections. Estonia, a small Eastern European country, has been voting online since 2007. In Brazil, the first step in that direction came from the National Congress, which has been voting remotely during the pandemic. Our deputies and senators are in the home office.

They plus six out of ten Brazilians. This is the crowd that was working from home in March, according to monitoring company Hibou. And many will continue to do so. In 2019, 45% of companies already allowed some kind of home office, according to the Brazilian Telecommuting Society. But this was seen as a privilege. "Now, it will be considered a working model", says Leonardo Berto, from HR consultancy Robert Half. Companies will rethink the need to maintain large, expensive offices - which should reduce traffic, pollution and energy consumption. But the work will not be entirely remote. Business meetings and fairs will have even more strength. “They will be opportunities for the creation of social networks, something that the virtual world does not offer in the same way”, says Berto.

We will come out of the pandemic injured, but also evolved. And the period of extreme isolation, paradoxically, can end up having the opposite effect: reinforcing social communion. It happened in China, the first country to contain the crisis. On April 4, the first day without quarantine, crowds filled the parks, sights and public spaces in the cities. People were desperate to leave the house. But also to celebrate, in a collective apotheosis, the only acceptable outcome: the victory of humanity over the virus.